In the early 1890s the financial situation was becoming serious. The Paige compositor, Webster & Company, and the cost of maintaining the Nook Farm lifestyle at the Hartford House, brought Sam to the brink of personal bankruptcy. To reduce their living costs, Sam closed down the Hartford House in June of 1891 and took the family to Europe, living in France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy.

Though burdened financially, Sam continued to work on a number of novels and sketches, publishing The American Claimant in 1892. He returned to New York often on business and in the fall of 1893 met Henry Huttleston Rogers, vice-president of Standard Oil and one of the wealthiest industrialists in America. Rogers admired Twain’s writing and soon provided valuable financial guidance. America was experiencing economic uncertainty following the collapse of the New York stock exchange that June. In early 1894, the failure of Webster & Company loomed. Some publications had not paid, a bookkeeper had embezzled $25,000, and Sam had used company assets for the Paige compositor. Sam gave Rogers power of attorney, which Rogers used to transfer all of Sam’s copyrights to his wife Livy. And when Webster & Company went bankrupt, Rogers had Livy declared the company’s primary creditor.

That year Sam finally abandoned the Paige compositor after a second model was tested unsuccessfully at the Chicago Herald, where 32 linotypes were already running smoothly. Rogers, who had also invested and who witnessed the test with Sam, advised that it had no commercial future.

Both Tom Sawyer Abroad and Pudd’nhead Wilson were published in 1894, and the Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc in 1895.

There was insufficient income, however, to pay his debts. Though few of Sam’s 96 creditors pressed him, and most agreed to settle for only 50cents in the dollar, Sam was determined to repay them in full. Henry Rogers arranged a plan that would allow Sam to do so, and in 1895-96, Sam undertook his most extensive lecture tour ever, around the world.

Between July of 1895 and July of 1896, Sam circumnavigated the globe fulfilling a demanding lecture itinerary. The tour route began in Paris, proceeding westward. The Clemens family stayed together until Susy and Jean chose to remain in Elmira with their aunt Susan Crane. Sam, Livy and Clara continued across America to British Columbia, sailing from Vancouver to Australia, New Zealand, India, Ceylon, Mauritius, South Africa, and England.

Sam intended to resettle the family in Guilford, England, but now news came that Susy was ill in Hartford, facing a long recovery. Livy and Clara at once embarked for home, but they had not yet reached New York when, in mid-August, 1896, Sam received a telegram at Guilford revealling that Susy had died of spinal meningitis. This was a tragic blow from which Sam never really recovered. When he eventually returned to Hartford, he was unable to enter the house, and the Clemens family never lived there again.

Livy and his other daughters rejoined Sam in Guilford in late September, and in October they relocated to the Chelsea district of London, near the River Thames. During the next ten months, Sam worked on Following The Equator which was published in 1897. It was his most elaborate travel book, with numerous illustrations, and, for the first time, photographs. After finishing his book, Sam moved the Clemens family to Switzerland in July 1897. The success of the round-the-world tour and the book, meant that by early 1898 Sam was able to repay his debts in full, a feat that won him considerable public admiration.

After two years in Europe, writing, lecturing, and meeting such notables as Sigmund Freud and Emperor Franz Josef 1 of Austria-Hungary, Sam took his family to London in July of 1900, living at Dollis Hill for three months. Busy writing and ever popular, Sam socialized with the cultural elite, and accepted numerous invitations to speak at banquets and public meetings.

In October of 1900, the Clemens family finally returned to America, moving into a house in Riverdale, just outside New York City, in 1901. Sam lectured extensively, taking an active role in New York’s social scene. He was presented with an honorary Doctor of Letters from Yale University in 1901.

That same year he became Vice President of the Anti-Imperialist League ~ a position he would hold for the next 9 years. He published To The Person Sitting in Darkness, and wrote The United States of Lyncherdom, decrying an appalling spate of lynchings.

A Double-Barrelled Detective Story and Was It Heaven? or Hell? were both published in 1902.

In April of 1902, Livy arranged the purchase of a house at Tarrytown, N.Y., overlooking a beautiful stretch of river, the Tappan Zee. The Clemenses, attracted by the Hudson environment, planned to make this their first permanent home in many years. Unfortunately, Livy’s declining health would prevent them from occupying the house.

The University of Columbia, Missouri, also in April of 1902, presented Sam with an honorary Doctor of Laws, for which he travelled back to the Midwest, staying from May 29 to June 3. Arriving in St. Louis, he was met at the train by his old river pilot instructor and friend Horace Bixby, as fresh and wiry as he had been forty-five years earlier. Bixby took him to the Pilot’s Association, where rivermen, soon hearing of Sam’s return, gathered to celebrate.

That same afternoon he took the train on an unplanned visit to Hannibal. A hotel clerk, recognizing him at once, gushed: “I’ve visited the house where you were born many times.” Sam quipped back: “I wasn’t born many times, just once.”

It was a poignant experience, returning to the scenes of his childhood and youth. He enjoyed reunions with boyhood friends, spoke to crowds of adoring citizens at functions, handed out diplomas to graduation students at Hannibal High School, posed patiently for photographers in front of his boyhood home, and visited the family plot at Mount Olivet Cemetery. He walked with boyhood playmate John Briggs on Holliday’s Hill, reminiscing fondly, as the river rolled by, rippling in the balmy Sunday afternoon sun. These encounters wrenched his heart. He was sure that he would never return.

All too soon, he was farewelled at the station. Just before boarding the train, a familiar figure pushed through the crowd. It was Tom Nash, a childhood friend ~ now deaf. Sam recalled: “He was old and white-headed, but the boy of fifteen was still visible in him. He came up to me, made a trumpet of his hands at my ear, nodded his head toward the citizens, and said, confidentially ~ in a yell like a fog horn ~ ‘Same damned fools, Sam.'”

At the University of Columbia, Missouri, Sam accepted his degree amid great praise, and later re-christened the St. Louis harbor-boat ‘Mark Twain’, taking a turn at the pilot wheel one last time.

Shortly afterward, the family took a summer cottage at York Harbor, Maine. During this period, the Hartford House was sold, as the family looked forward to making a new permanent home at the Tarrytown house. But in August, Livy became seriously ill and on medical advice spent long periods of isolation in York Harbor and Riverdale, before being advised to seek the warmer climate of Florence, Italy, in late 1903. On August 24, Sam and Livy sailed for Florence, with daughters Clara and Jean, Katie Leary (in their domestic service 23 years) and a trained nurse. Livy died in Florence on June 5, 1904. The family returned with her remains to Elmira.

The Tarrytown house could now never be the home he and Livy had planned, so Sam sold it before the end of 1904. He lived in New York, in a brownstone at 21 Fifth Avenue, writing and making public appearances. By this time, he was a national hero, and he used his recognition to speak out against injustice and intollerence. So much so that some suggestions were made as to his Presidential worthiness, which he easily dampened, for he was wise enough to the ways of politics.

In 1904, he published Extracts from Adam’s Diary. On the occasion of his 70th birthday, he attended a banquet in his honor at Delmonico’s in New York.

Also in 1905, biographer Albert Bigelow Paine joined the family household. Sam published The Czar’s Soliloquy and King Leopold’s Soliloquy and spent the summer at a house in Dublin, New Hampshire. In November of 1905, he dined at the White House with Theodore Roosevelt.

In 1906, he testified before Congress on Copyright legislation, wearing a white suit, beginning his trademark wearing of a white suit year-round. He published What is Man?, Eve’s Diary, and The $30,000 Bequest. And in 1906~07 Chapters From My Autobiography appeared

On June 26th, 1907, he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Literature degree by the Oxford University (along with Rudyard Kipling, Auguste Rodin the sculptor, and Camille Saint-Saens). Several months earlier, C.F. Moberly Bell, the Editor of the London Times, had asked him when he would return to England. Sam had previously said that he would never travel abroad again, and reportedly answered: “When Oxford bestows its degree upon me!” The cable from Oxford arrived in May, so Sam sailed once more for England.

He was received triumphantly. From the moment he disembarked, throngs of reporters and photographers surrounded him. The dock stevedores gave him a round of cheers. “They stood in a body on the dock and charged their masculine lungs, and gave me a welcome which went to the marrow of me.”

Quote: ~

Mark Twain’s bursting upon London society naturally was made the most of by the London papers, and all his movements were tabulated and elaborated, and when there was any opportunity for humor in the situation it was not left unimproved. The celebrated Ascot racing-cup was stolen just at the time of his arrival, and the papers suggestively mingled their head-lines, “Mark Twain Arrives: Ascot Cup Stolen,” and kept the joke going in one form or another.

Credit: ~ Mark Twain: A Biography, by Albert Bigelow Paine.

The accolades were unending, and he was overwhelmed with invitations to a variety of functions over an extended stay of 26 days, including a royal banquet with King Edward V11 and the Queen, and an unprecedented dinner with the staff of Punch magazine.

He had hoped to seclude himself away from the fuss, but realized it would not be possible to deny the outpouring of praise and affection that sought him out so keenly. So much mail arrived at his hotel ~ letters, gifts, invitiations, that it was jokingly compared to a Post Office. Together with a Secretary ~ keeping track of his engagements, he paid numerous visits, to the homes of the poor and the rich alike, showing no partiality.

It was the culmination of his career to recieve honors from Oxford, but a more touching reward was the sincere affection and love so freely bestowed upon him by countless people, from stevedore to King. “Praise is well, compliment is well, but affection—that is the last and final and most precious reward that any man can win, whether by character or achievement, and I am very grateful to have that reward. ”

When he sailed for home on July 13th, multitudes lined the dock to glimpse him, to shout, to wave a final good-bye. “It has been the most enjoyable holiday I have ever had, and I am sorry the end of it has come. I have met a hundred old friends, and I have made a hundred new ones. It is a good kind of riches to have; there is none better, I think.”

The London Tribune reported: “the ship that bore him away had difficulty in getting clear, so thickly was the water strewn with the bay-leaves of his triumph. For Mark Twain has triumphed, and in his all-too-brief stay of a month has done more for the cause of the world’s peace than will be accomplished by the Hague Conference. He has made the world laugh again.”

He arrived back in New York ahead of schedule, inviting his biographer, Albert Bigelow Pain, to come and play billiards.

Quote: ~

I confess I went with a certain degree of awe, for one could not but be overwhelmed with the echoes of the great splendor he had so recently achieved, and I prepared to sit a good way off in silence, and hear something of the tale of this returning conqueror; but when I arrived he was already in the billiard-room knocking the balls about—his coat off, for it was a hot night. As I entered he said: “Get your cue. I have been inventing a new game.” And I think there were scarcely ten words exchanged before we were at it. The pageant was over; the curtain was rung down. Business was resumed at the old stand.

Credit: ~ Mark Twain: A Biography, by Albert Bigelow Paine.

Quote: ~

There followed another winter during which I was much with Mark Twain, though a part of it he spent with Mr. Rogers in Bermuda, that pretty island resort which both men loved. Then came spring again, and June, and with it Mark Twain’s removal to his newly built home, “Stormfield,” at Redding, Connecticut. The house had been under construction for a year. He had never seen it– never even seen the land I had bought for him. He even preferred not to look at any plans or ideas for decoration. “When the house is finished and furnished, and the cat is purring on the hearth, it will be time enough for me to see it,” he had said more than once.

Credit: ~ The Boys’ Life of Mark Twain, by Albert Bigelow Paine.

He intended the Redding house to be a summer residence, but changed his mind soon after taking possession on the 18th of June, 1908, standing in his own home for the first time in seventeen years. The house was completely finished, and furnished to the last detail. He was immediately charmed by the restful, home-like atmosphere of the house, and by the beautiful vista of treetops and blue hills that surrounded it.

He called the house “Innocents At Home”, but after publishing Captain Stormfield’s Visit To Heaven that year, and witnessing the majestic summer storms of the area, he decided ‘Stormfield’ was more appropriate.

Quote: ~

Mark Twain loved Stormfield. Almost immediately he gave up the idea of going back to New York for the winter, and I think he never entered the Fifth Avenue house again. The quiet and undisturbed comfort of Stormfield came to him at the right time of life. His day of being the “Belle of New York” was over. Now and then he attended some great dinner, but always under protest. Finally he refused to go at all. He had much company during that first summer ~ old friends, and now and again young people, of whom he was always fond. The billiard-room he called “the aquarium,” and a frieze of Bermuda fishes, in gay prints, ran around the walls. Each young lady visitor was allowed to select one of these as her patron fish and attach her name to it. Thus, as a member of the “aquarium club,” she was represented in absence. Of course there were several cats at Stormfield, and these really owned the premises. The kittens scampered about the billiard-table after the balls, even when the game was in progress, giving all sorts of new angles to the shots. This delighted him, and he would not for anything have discommoded or removed one of those furry hazards. My own house was a little more than half a mile away, our lands joining, and daily I went up to visit him–to play billiards or to take a walk across the fields. There was a stenographer in the neighborhood, and he continued his dictations, but not regularly. He wrote, too, now and then, and finished the little book called Is Shakespeare Dead?

Credit: ~ The Boys’ Life of Mark Twain, by Albert Bigelow Paine.

Quote: ~

Comets in particular interested him, and one day he said: “I came in with Halley’s comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don’t go out with Halley’s comet.” He looked so strong, and full of color and vitality. One could not believe that his words held a prophecy. Yet the pains recurred with increasing frequency and severity; his malady, angina pectoris, was making progress. And how bravely he bore it all! He never complained, never bewailed. I have seen the fierce attack crumple him when we were at billiards, but he would insist on playing in his turn, bowed, his face white, his hand digging at his breast.

Credit: ~ The Boys’ Life of Mark Twain, by Albert Bigelow Paine.

His youngest daughter, Jean, joined him as his secretary, and Clara married Ossip Gabrilowitsch (a Russian musician) at Stormfield in 1909. Sam wore his Oxford robes at the wedding. That year, Sam published ‘Letters From The Earth’. He was looking forward to a pleasant Christmas, but Jean, who had developed epilepsy in the late 1890s, had a seizure on Christmas Eve and died suddenly. Sam was devastated. He grieved by writing The Death of Jean expressing his accumulated grief over the loss of Jean, Livy, Susy and his infant son. It was his last substantial piece of writing. He vowed never to write again. His health now declined in sympathy with his spirit.

In January of 1910, he went to Bermuda for his health, but sensing his weakening condition he returned to Stormfield where he sank into a coma on April 21, 1910. That same night his heart failed and he died in his bed. Two days later a large funeral procession was held in New York City, with a service at the Presbyterian Brick Church. He was buried next to his wife and children at Woodlawn Cemetery, in Elmira, N.Y.

Halley’s Comet appeared in the April skies at the time of his death, just as it had appeared at the time of his birth in November of 1835. His prediction had come true.

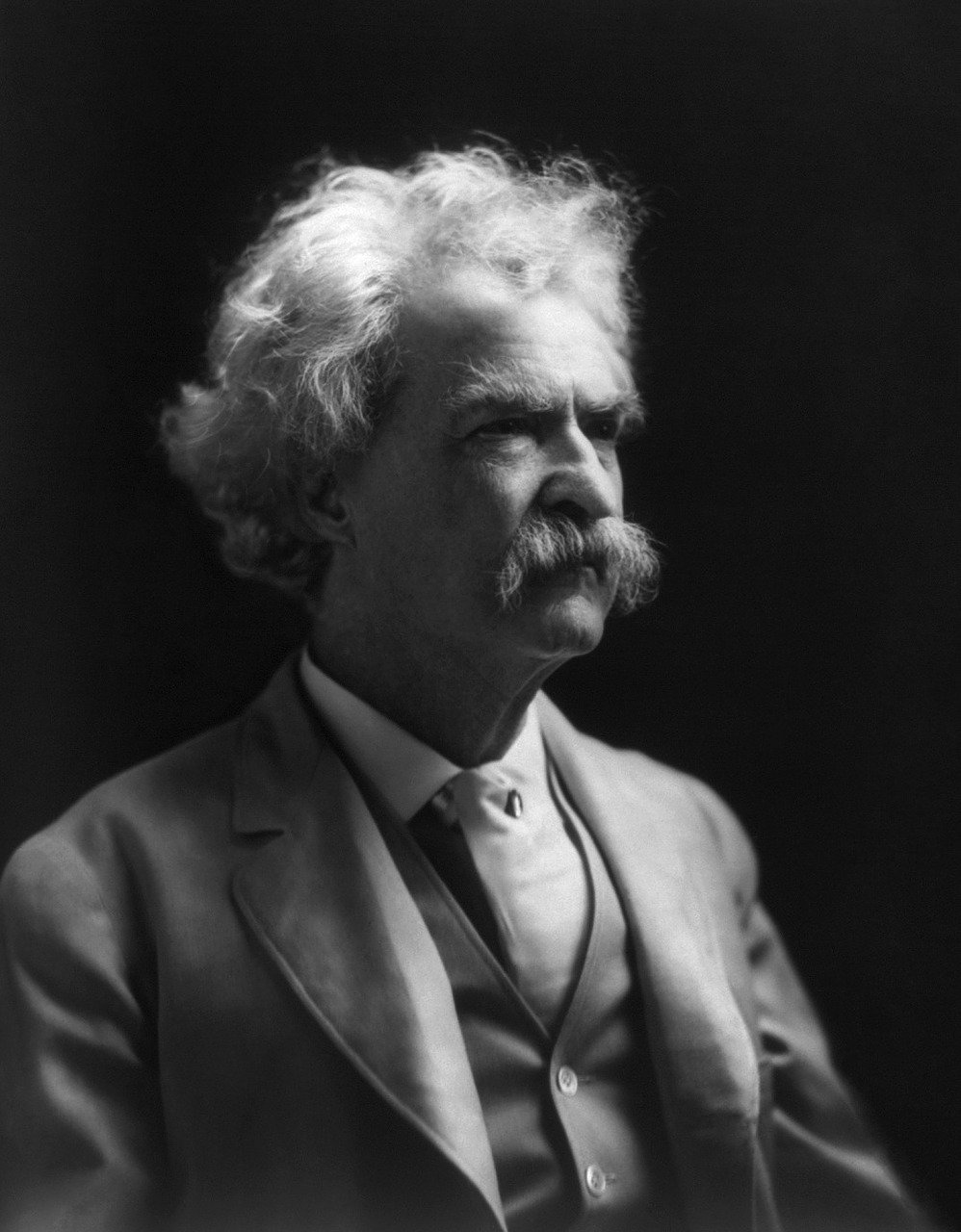

Twain’s life and works were defined by his early experiences in Hannibal and the West. The barefoot boy and the riverboat pilot always remained within. Livy, knowing this, had always called him “Youth”. His insights and his humanity combined in his writing to uncover the American experience with accuracy and heart. He was admired with affection throughout the world as a humorist during his life, and since his death, his reputation has only grown.