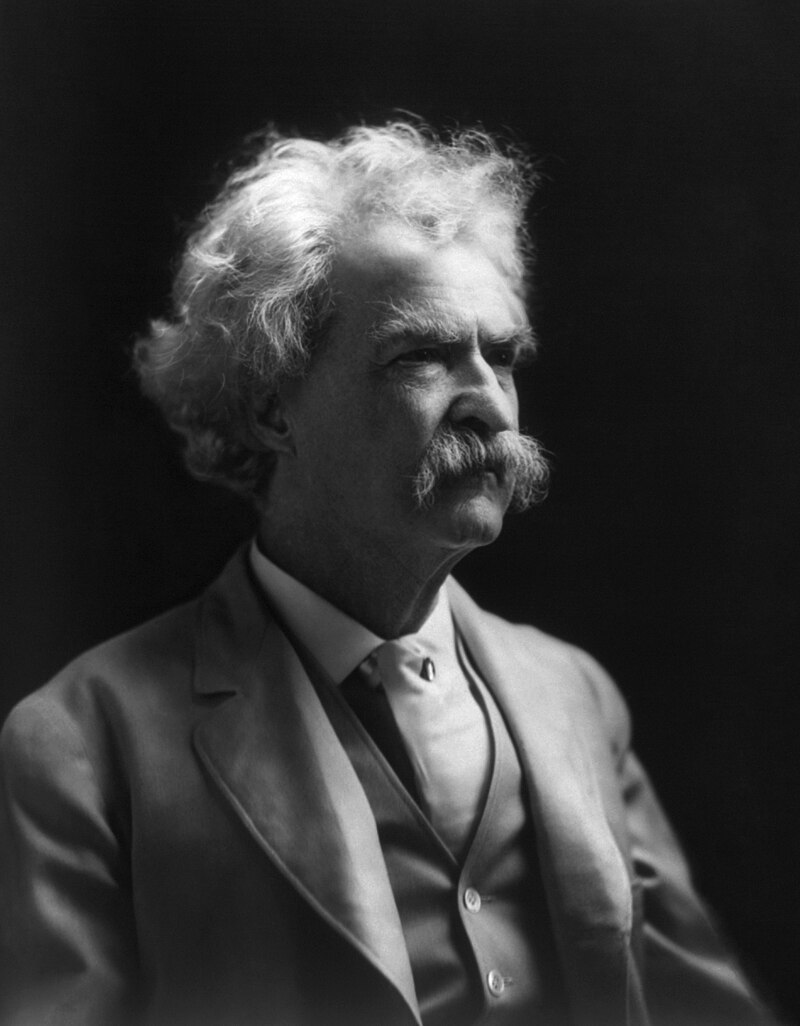

Samuel Clemens, born on November 30, 1835, the sixth child of John and Jane Clemens, in a cabin in the small settlement of Florida, Missouri.

The family moved to nearby Hannibal in 1839, where Sam spent his boyhood in the presence of the broad Mississippi, and the captivating steamboating times that would so fondly influence his life. His father’s death in 1847 brought hardship, and in 1848 he began work as a printer’s apprentice for Joseph Ament, who published the Missouri Courier. This daguerreotype was created in December, 1850, when Sam was 15 years old. He is wearing a printer’s cap and holding a printer’s composing stick with his name spelled in type. He set the letters in reverse so that they would read correctly when the daguerreotype produced a mirror image. When he was 16, in 1851, he began typesetting for his brother Orion, on the Hannibal Journal, which they later set up in their home. Sam began contributing humorous pieces, and occasionally stood in as Editor when Orion was away. During 1852, Sam contributed several sketches to the Philadelphia’s Saturday Evening Post.

There is an original daguerreotype which was probably treated in gold chloride tones measuring some 6cms x 7.5cms which was mounted in a handsome case, as was the custom. The delicate image survives, somewhat damaged, in the care of the Bancroft Library.

Note:~ A daguerreotype is an early type of photograph in which the image is exposed directly onto a mirror-pollished surface of silver, bearing a coating of silver halide particles deposited by iodine vapour. Later, bromine and chlorine vapours were used to shorten the exposure time. It is a direct positive image process with no “negative” original that can be used to make copies. The short exposure time made the daguerreotype the first commercially viable photographic process. They were, however, very delicate, requiring a glass case. The 1850 image of Sam is sometimes referred to as a tintype ~ this is incorrect, as the tintype process was invented in 1856.

Sam left Hannibal for the first time in June of 1853, when he was seventeen, working initially in St. Louis as a typesetter for a few months. By late August he was heading to the World’s Fair in New York City. When he arrived, he wrote to his mother: “You will doubtless be a little surprised and somewhat angry when you receive this, and find me so far from home. . . . Well, I was out of work in St. Louis, and didn’t fancy loafing in such a dry place, where there is no pleasure to be seen without paying well for it, and so I thought I might as well go to New York. I packed up my ‘duds’ and left.”

New York’s frenetic variety was fascinating, but the nefarious quarters were equally appalling. He was captivated by the dichotomy of the populace. In a letter to his sister, Pamela Moffett, in St. Louis, he wrote: “I have been fooling myself with the idea that I was going to leave New York, every day for the last two weeks. I have taken a liking to the abominable place.” He lingered until late October, when he travelled to Philadephia, working again as a journeyman printer.

The next three and half years found him moving between New York, Philadephia, Washington D.C., Muscatine (Iowa), St. Louis, Keokuk (Iowa), and Cincinnati.

In February of 1857, he took passage on the Paul Jones from Cincinnati to New Orleans, intending to embark for the Amazon River, to seek his fortune in the thriving coca trade. He was twenty-one years old. His plans changed when he met pilot Horace Bixby. Before reaching New Orleans, Sam’s boyhood dream to become a steamboat pilot had been revived. He convinced Bixby to take him on as a Cub Pilot for $500, with $100 in advance and the balance from future wages.

After two years as a Cub Pilot, Sam was granted his license on April 9, 1859, at the age of 23. He would be a pilot for another two years, and unlike many of his contemporaries, he worked steadily on many of the Mississippi’s finest boats due to his reputation as a safe helmesman.

Sam relished the steamboating life; the ever-changing scenes, the travellers coming and going, the cursing, swearing Mates as they rushed to move freight, the good-natured stewards, the bells and noises that stirred him from sleep, the many landings, the moonlit nights, the enchanting dawns over the river, and the pilots and visitors yarning in the pilot-house. It was a life that he seemed born to.

Quote: ~

I loved the profession far better than any I have followed since, and I took a measureless pride in it. The reason is plain: a pilot, in those days, was the only unfettered and entirely independent human being that lived in the earth.

Credit: ~ Chapter 14, Life On The Mississippi, by Mark Twain.

In April of 1861, when the Civil War caused the suspension of civilian river traffic on the Mississippi, Sam’s career as a steamboat pilot came to an abrupt end. He joined a volunteer militia called the Marion Rangers, which drilled for two weeks before disbanding. In the summer of 1861 he found himself on a stagecoach heading west with his older brother Orion, who had been appointed Secretary of the Nevada Territory.

Prospectors were flocking to the region’s gold and silver strikes, in areas including Humboldt, Esmeralda, and Aurora. Before long Sam was trying his luck. By about April of 1862, he was prospecting near Aurora, and it was now that he began contributing humoruous letters to the Virgina City Territorial Enterprise signed “Josh”. These were so popular that owner Joe Goodman offered Sam $25 a week to work for the newspaper, an offer he later increased to $40. In late September, Sam arrived in Virgina City to begin his seventeen month stint with the paper, thriving on the literary freedom it afforded. This was one of the busiest and happiest periods of his life, recalled with enthusiasm in chapters 42 and 45 of Roughing It. He began using the pen-name Mark Twain.

In May of 1864, he headed for San Francisco, working for the San Francisco Morning Call newspaper as a full-time reporter, and later as the Pacific correspondent for the Territorial Enterprise. He wrote for a number of publications including the Californian and The Golden Era.

In 1865, he visited Jackass Hill, California, where he tried gold-mining and heard the Jumping Frog story, writing Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog, a popular sketch that was widely published. The next year, in 1866, he travelled to the Sandwich Islands writing for the Sacramento Union, and upon returning to California gave his first lecture on his travel experiences.

Sam left San Francisco for New York at the end of 1866, via Nicaragua. In 1867, he undertook a Midwest lecture tour with stops in St. Louis, Hannibal, Quincy and Keokuk, published The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, and was commissioned to be a travel writer for the San Francisco Alta California aboard the Quaker City, an excursion to the Mediterranean and back from June 8 to November 19 of 1867.

On board the Quaker City, in 1867, Sam met Charles Langdon who showed him an ivory miniture of his sister ~ Livy. From that moment, he was so charmed that he asked to see it repeatedly. He met Livy near the end of that year when he dined with the Langdom family in New York, and escorted Livy to hear Charles Dickens read. The following year, he visited the Langdon summer home in Elmira several times. He saw her as the epitomy of femine refinement and delicacy, and appealed to her to “refine” him.

During 1868, while courting Livy, he received a contract for his first book, The Innocents Abroad which he completed in San Francisco, along with several published sketches. His first proposal to Livy in September of 1868 was rejected, after which he undertook a lecture tour through California and Nevada in November and December. In February of 1869 he proposed to Livy again. Their engagement was formally announced after her father had quietly checked Sam’s “references”. The lectures tours continued throughout 1869, when Sam also published Innocents and bought a share in the Buffalo Express. Sam and Livy were married on February 2nd, 1870.

After Sam’s marriage to the 25-year-old Livy, the couple settled in Buffalo, N.Y., in a house that was a wedding present from Livy’s father. Sam edited on the Express, wrote a monthly column for a New York literary magazine called the Galaxy, and began working on an account of his experiences in Nevada and California that would become Roughing It. He completed another lecture tour between November 1869 and January 1870.

But 1870 would become a difficult year for Sam and Livy. Their first child, son Langdon, was born premature and remained sickly. Next Livy’s father died, followed by her close friend while staying in the Buffalo home.

In 1871, encouraged by Hartford’s literary notables, Sam leased a house in the Nook Farm neighbourhood and bought land beside Farmington Avenue on which to build a home. He continued his lecture tours and visited England for the first time.

The following year, in March of 1872, Susy Clemens was born. Sam, now 38-years-old and becoming a literary celebrity, returned to England with his family in 1873, meeting literary society favorites such as Ivan Turgenev, Robert Browning, Anthony Trollope, and Lewis Carroll.

That year saw the publication of his first work of fiction, The Gilded Age written in collaboration with Charles Dudley Warner, and Sam recieved a patent for a self-pasting scrapbook that would earn him a modest sum over many years. Also in 1873, Sam engaged New York architect, Edward Tuckerman Potter, to design a house for their Nook Farm property. Olivia sketched a layout of the rooms relating to the views over the then open countryside. The Clemens family moved into the finished house during September of 1874.

In June, Sam and Olivia’s second daughter, Clara, was born. Sam now settled into a most productive period, discovering the literary treasure of his youth, and the Mississippi. Old Times on the Mississippi, a series of sketches, appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in 1875. His thoughts had returned home, and in 1876 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was published.

The Clemens family lived a year and a half in central and southern Europe, in 1878-79, so that Sam could gather material for another travel book, A Tramp Abroad, published in 1880, the same year that third daughter, Jean, was born.

A year later, The Prince And The Pauper was published, representing Sam’s first serious theme. While working on Pauper he had begun writing “by fits and starts” a sequel to Tom Sawyer, (Huckeberry Finn), but time and again he had put it aside.

After an absense of 21 years, Sam finally returned to the Mississippi in April of 1882, on a 6-week steamboat journey gathering material for Life On The Mississippi, published a year later. This journey, which included a nostalgic visit to Hannibal, gave new life to Huck and in December of 1884 The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was published.

Huck Finn was published by Charles L. Webster & Company, a publishing firm Sam had founded in May of 1884, having been dissatisfied with most of his earlier publishers. The firm enjoyed initial success after the publication of Ulysses S. Grant’s memoirs in 1886, and with further editions of Sam’s earlier books.

From November 1884 to the end of February 1885, Sam undertook a North American lecture tour with George Washington Cable, through the East and Midwest.

In early 1886, Sam bought a half interest in the Paige compositor ~ an automatic typsetting machine, having begun investing in the machine in 1880 soon after meeting inventor James Paige in Hartford. Sam, as Paige’s partner, now supported his work at the rate of $3,000 per month. The first working model of the compositor was built in 1887, and after further work it set justified type in 1887. Though a third faster than its competition, the linotype, it was beset with unreliability, and though frustrated by delays Sam was repeatedly convinced by Paige to continue investing.

Sam published a satirical classic A Connecticut Yankee In King Arthur’s Court, in 1889.