Racing is undoubtedly one of the most thrilling sports, leaving spectators at the edge of their seats while unleashing the competitive nature and skills of its participants. From horse racing, kart racing, drag racing, swimming, dragon boat racing, marathons, to Formula One, there are lots of forms of sports racing, all promising the same excitement in every race. But, have you ever wondered if steamboats were used for sports racing? Well, let’s delve into that and discover more about the esteemed history of steamboat racing that once brought amusement and fanfare to the country’s rivers.

History of Steamboat Racing

River travel has been the lifeblood of transportation and trade in the United States, prior to the invention of railroads, cars, and airplanes. Boats transported people to their destination, allowed the exchange of goods, as well as supported the nation’s expansion and development.

With the arrival of the boiling steam engine in the early 19th century, moving through rivers became more efficient and faster, as it was no longer dependent on river currents. More notably, river travel has become more profitable and commercially successful with the drastic cut in travel time.

Yet, like with any industry, part of ensuring greater revenue was being on top of the competition. As steamboats became abundant by the 1820s, competition also grew aggressively between captains. They employed different tactics to topple other steamboats but primarily focused on speed, given that it was the biggest factor that would entice passengers. Advertisement claiming that they were the fastest vessel graced newspapers, signaling a “virtual race” between the steamboats.

The earliest forms of steamboat races were pretty informal and spontaneous. Two captains who happen to be along the same river stretch often randomly decide to get into a race.

Such impromptu events, however, turned out to be epically catastrophic. To win the race, the captain would order their engineer to stoke the steamboat higher and close the safety valve to make it faster. The problem was it often placed great pressure on what the boiler could handle, rapidly deteriorating its quality and eventually leading to explosions. Not to mention that there were also risks of collisions and groundings during the race, further putting the vessel in peril.

Nevertheless, the bravado of being the fastest boat and the profitability overshadowed such dangers. Steamboats became daredevils and captains were always on the chase to break records, often driving their vessels to the limit. Placing safety only as a secondary concern, steamboat racing proved to be a hazardous sport by the 1830s to the 1840s.

After many catastrophic events and inevitable deaths, Congress passed the Steamboat Acts (1838 and 1852) to regulate safety on these vessels. It entailed boat licensing, the establishment of inspection services, and legal sanctions on all forms of negligence. As such, accidents resulting from racing decreased significantly in the 1860s.

While risks were ineluctable, the popularity of steamboat racing never really dwindled. Later on, racing became pre-planned and more formal. They were advertised immensely, increasing public excitement. People laid bets on these races, with the elite even shelling out large sums of money for the most famous steamboats. Not only steamboat races became a sport, but it was integrated into the people’s culture during its heyday, often celebrated with appropriate splendor.

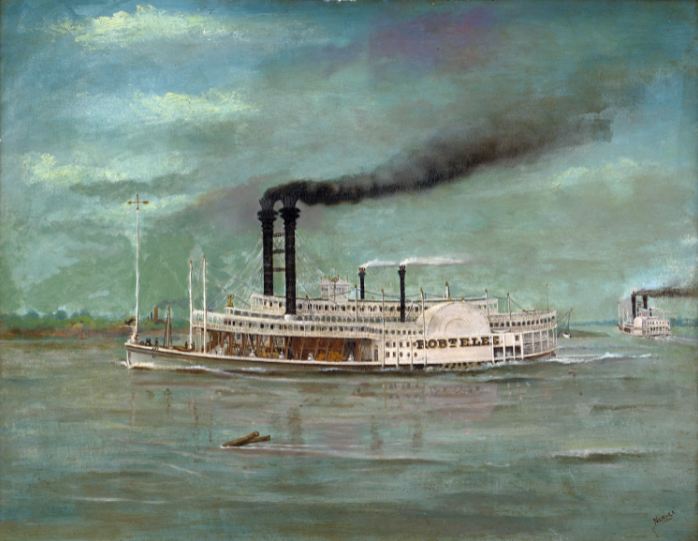

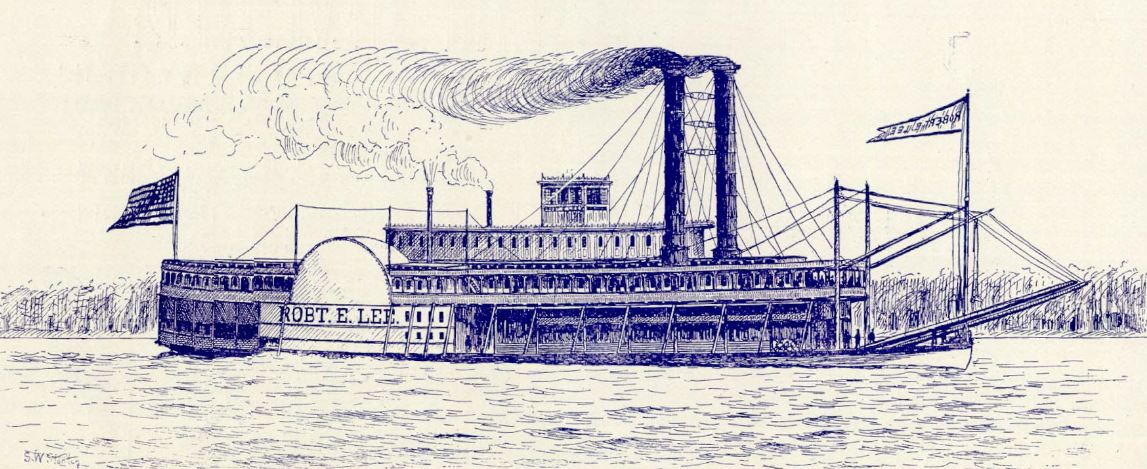

The most famous of all the steamboat races was “The Mississippi Steamboat Race of 1870” between Robert E. Lee and the Natchez. Prior to the event, its captains, Captain John W. Cannon from New Orleans, Louisiana, and Captain Thomas P. Leathers from Natchez, Mississippi respectively, already had an ongoing rivalry in getting the biggest share of the passengers and trade.

While they began as business partners, the competition was fierce between the two, even engaging in a street brawl at some point. Given such, a steamboat race was just imminent.

Early in the evening of June 30, 1870, the steamboats departed from New Orleans onto the finish line in St. Louis, Missouri. The event was received with much fanfare, with newspapers also publicizing the contest. Of course, bets were overflowing even in European countries.

Capt. Cannon got an early lead and by mid-morning the next day, Robert E. Lee still got its nose ahead. However, the crowd was unsympathetic when the steamboat was passing through in Natchez. Of course, people expected to see the steamboat bearing their community’s name to be ahead, but only to witness Lee come in first.

By the second night, Natchez seemed to be catching up with its rivals but a broken valve hurt its chances, impeding the steamboat for about half an hour to do the repairs. Meanwhile, Cannon had a smart tactic, as he took fuel from other boats and barges while the race was underway. On the other hand, Natchez preferred to make periodic stops to refuel.

Lee was still ahead for more than an hour as they reached Memphis, Tennessee. Another unfortunate event happened for Leather after Nathcez’s water pump broke in Mississippi, causing another over an hour of repair time. The fog then shrouded its way in Missouri, further delaying Natchez for about six hours. By the time it lifted, Cannon already had an insurmountable lead.

On July 4th, 1870 at 11:14 AM, Robert E. Lee arrived at St. Louis, winning the race against Natchez who came six hours later and setting a still-standing record of three days, 18 hours, plus 14 minutes for the said distance for steam engine-powered, paddle wheelers.

The victory, however, wasn’t accepted by all. Without the stops and the fog, Natchez had finished the race 28 minutes shorter than Lee. As no clear-cut rules were set, the true victory remains a hot issue for debate for many enthusiasts today.

As the Industrial Revolution peaked, railroads took the place of steamboats as the most preferred way of transportation, eventually leading to the end of the Steamboat Era. The last race occurred in Louisville, Kentucky on August 19, 1929, between America and Cincinnati, with the latter winning the close race from 2nd Street to Rose Island Amusement Park.

In 1963, Louisville revived the tradition with the Great Steamboat Race, which has since become an annual event leading to the Kentucky Derby Festival. The race first saw epic and fierce battles between equally-matched steamers Delta Queen and Belle of Louisville. Through the years new boats joined the fleet while some were replaced, but the same spirit and heritage of steamboat racing live on.